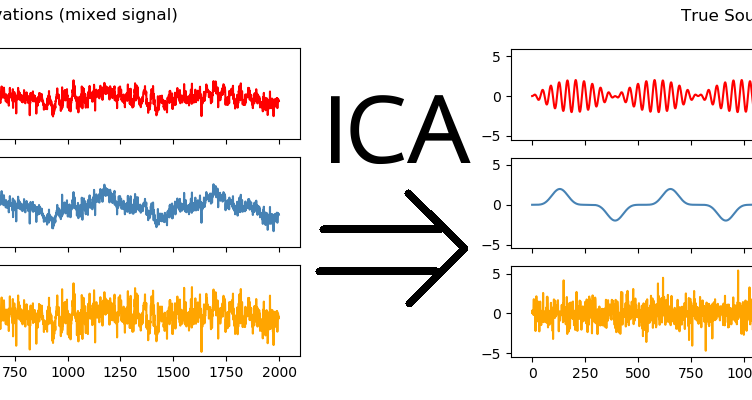

Independent Component Analysis (ICA) is an unsupervised learning technique designed to separate a multivariate signal into a set of additive, statistically independent components. In plain terms, ICA tries to “unmix” signals that have been combined together. This is useful when you observe mixtures (like several voices recorded by multiple microphones) and want to recover the original sources. Unlike many dimensionality reduction methods that focus on variance, ICA focuses on independence and non-Gaussian structure in the data. If you are studying unsupervised methods through a data science course in Chennai, ICA is a practical concept because it connects probability, optimisation, and real-world signal problems in a clean, learnable way.

1) What ICA Is Trying to Achieve

ICA assumes that the observed data is generated by mixing a set of hidden source signals. Mathematically, you can think of it like this: you observe a matrix X (your recorded signals), which is a product of an unknown mixing matrix A and unknown independent sources S. The task is to estimate an “unmixing” transformation that recovers S from X.

The key goal is statistical independence. Independence is stronger than uncorrelatedness. Two signals can have zero correlation and still be dependent. ICA aims to find components where knowing one component gives you no information about another.

Why “non-Gaussian” matters

A major insight behind ICA is that mixtures of independent signals tend to look “more Gaussian” than the original sources (this is related to the Central Limit Theorem). Therefore, ICA searches for directions in the data that maximise non-Gaussianity, because those directions are likely to correspond to the original independent sources.

2) Core Assumptions and Intuition

ICA is powerful, but it relies on assumptions. Understanding these helps you know when ICA will work well and when it may fail.

Assumption A: Sources are independent

ICA works when the underlying sources are statistically independent. For example, different speakers talking at the same time are often treated as approximately independent sources.

Assumption B: At most one source is Gaussian

If all sources are Gaussian, ICA cannot uniquely identify them, because Gaussian variables remain Gaussian under many linear transformations. The “non-Gaussian” condition is not a minor detail; it is what makes separation possible in practice.

Assumption C: Mixing is approximately linear and instantaneous

Classic ICA assumes the observed signals are linear mixtures of sources at the same time step. Some real systems have delays or convolutions, and those require extensions of ICA.

These assumptions are often explained in the context of a data science course in Chennai because they train you to check model fit before applying a technique blindly.

3) How ICA Works in Practice

Most ICA workflows follow a consistent pipeline. The specific algorithm can vary, but the structure stays similar.

Step 1: Centre the data

You subtract the mean so each feature has zero average. This simplifies later calculations and avoids unnecessary bias.

Step 2: Whiten the data

Whitening transforms the data so features become uncorrelated and have unit variance. This reduces the problem complexity by narrowing down the space of possible solutions. After whitening, ICA mainly needs to find a rotation that produces independent components.

Step 3: Optimise for independence (or non-Gaussianity)

Algorithms like FastICA are widely used because they are efficient and stable for many practical cases. FastICA typically maximises a non-Gaussianity measure (often based on approximations to negentropy). The optimisation iteratively adjusts the unmixing vectors until the extracted components become as independent as possible.

Output interpretation

ICA returns independent components and an estimated mixing/unmixing relationship. In applied settings, you usually examine components visually or statistically to confirm they represent meaningful sources, not noise.

4) Applications, Limitations, and Practical Tips

Common applications

- Blind source separation: Separating mixed audio sources, EEG/MEG brain signals, or sensor streams.

- Feature extraction: Creating components that can be used as inputs to downstream models, especially when signals are mixed.

- Noise/artifact removal: In biomedical signals, ICA can separate artifacts (like eye blinks in EEG) from neural activity.

- Exploratory analysis: Understanding hidden drivers in complex multivariate observations.

Limitations to keep in mind

- Not designed for clustering: ICA is not a replacement for k-means or density-based methods. It produces components, not clusters.

- Sensitivity to preprocessing: Poor centring/whitening or unscaled data can lead to unstable results.

- Component order and sign ambiguity: ICA components can be recovered up to permutation and sign changes. This is normal and not an error.

- May extract noise if assumptions don’t hold: If sources are not independent or the mixing is not linear, ICA may output components that are hard to interpret.

Practical tips

- Always standardise/whiten properly and inspect results.

- Try multiple random initialisations if results vary.

- Validate components using domain checks (plots, frequency analysis, correlations with known signals).

- Treat ICA as part of a pipeline, not a final answer.

If your goal is to build strong intuition on these trade-offs, a data science course in Chennai that includes hands-on signal or time-series exercises can make ICA far easier to remember and apply correctly.

Conclusion

Independent Component Analysis is a focused unsupervised learning method that separates mixed signals into independent, non-Gaussian components. Its strength lies in modelling independence rather than variance, which makes it valuable for source separation, artifact removal, and feature discovery in multivariate data. Like any technique, ICA works best when its assumptions roughly match reality, and when preprocessing is done carefully. With the right use case and validation, ICA becomes a practical tool you can confidently add to your unsupervised learning toolkit—especially when building applied skills through a data science course in Chennai.